Barriers to reporting: How does a ‘whole school approach’ to student safeguarding help ensure the quietest voices are heard?

Learner engagement and it’s positive impact

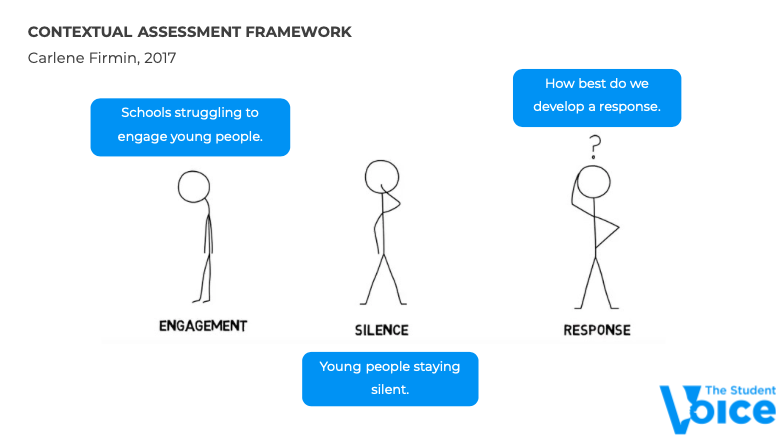

It is well researched that learner engagement has a positive impact on students, improving self-esteem, motivation, performance, behaviour, self-efficacy and relationships, to name a few. However, when it comes to safeguarding, the focus is predominantly on listening to adults. Currently, most safeguarding processes and systems focus on listening to adults in the community, and as Dr Carlene Firmin’s research (2017) suggests, students may not readily share such information with adults or feel too disengaged to do so.

Senior leaders, pastoral staff and teachers will always have the best interests of students in mind when making decisions about the organisation of a school. Building trust and opening up the discussion to students to share ideas, support each other and be involved in the process from the beginning is vital.

Get our blogs sent straight to your inbox.

Including them in the decision-making process when it comes to safeguarding their community places value in their opinions, but requires a whole-school approach or commitment in order to be effective. This means finding approachable ways in which students can put their views across.

Why are there barriers to reporting

There are a number of barriers to reporting when it comes to ensuring students feel able to communicate with teachers and education professionals. We’re essentially asking them to approach and talk to adults about issues they’re not necessarily comfortable discussing, with people they may not have as much contact with.

We continue to come back to the NSPCC safeguarding training questions that inspired The Student Voice tool. The first question asks you to tell an acquaintance something about yourself that you would be happy for anyone to know, which is relatively easy. The second asks, how would you feel towards telling an acquaintance something about yourself, that you would only tell your closest friend? This may be more difficult and you may feel uncomfortable doing so. Lastly it asks, would you want to come forward with something you wouldn’t want anyone to know about you? Something that is going on in your life right now, or has happened historically, but you feel you may need to share that in order to keep you safer.

That is, in essence, the challenge that we face with regards to safeguarding students in schools. There will be some trusting relationships, but do we have enough of those strong relationships for students to talk to teachers? And do we have enough avenues and different methods for students to communicate with teachers and Designated Safeguarding Leads about issues in their life?

Helping students communicate with other school stakeholders

There are a range of ways in which you can help students communicate with teachers and others within the school. Many young people find communicating using technology easier, having grown up with this as a standard way of interacting. Initiatives such as electronic suggestion boxes – where these issues can be put across in a more approachable way and then be addressed – have been shown to be effective and take away the stigma that may come from approaching a teacher or being seen at a physical suggestion box.

This also means that the younger and quieter students can feel equally heard. When you’re in the youngest year group or more of an introvert, it can be particularly intimidating to try and report areas in which you feel unsafe. The use of technology means that everyone’s voice carries the same weight, and gets equally heard. This input should be regularly reviewed in order to ensure students’ safety in as short a time frame as possible. Issues left unaddressed for long periods could mean increased risk, so systems such as student meetings every term may not address ongoing problems.

Student participation in our school culture

Contextual Safeguarding research shows adults don’t necessarily fully understand the life experiences of students, and that in order to change the context of where harm takes place, we need to understand the life experiences of our young people.

Anna Freud suggests including many different aspects of school life, like ‘the curriculum, how pupils like to learn, facilities and the physical environment of the school, break times, after-school clubs, uniform, welfare and bullying’, and ensuring ‘the value and ethos of the school reflects the commitment to listening to student voice’, whether that’s in ‘school statements, school action planning, the website, classrooms and any other publications that talks about whole-school values’

Incorporating student’s views through embedding a listening culture and involving young people in decision-making should be an integral part of a whole-school approach to safeguarding. A March 2021 survey by the Anna Freud Centre with 3000 young people aged between 11 and 19, revealed that “93% of children want mental health teaching to be brought into the classroom”. As we look further into the work of Professor Lundy and Hub na nÓg, with the Lundy Model of Participation as an organisation, we see the great potential of creating these brave spaces that will empower young voices and mould a stronger, more resilient school culture.